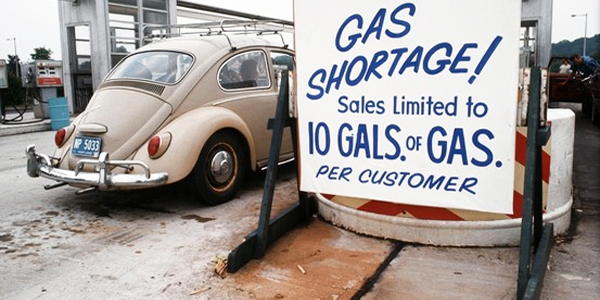

The doctor said there is no getting it up and out, that we have to wait until it went down and out. My Dad, swallowing gasonline when he tried to syphon some from the car to use in our lawn mower. This was during the gas rationing of the 70’s, when it wasn’t unusual to see people standing in the gasline without a car, but with a can, as their car was already long out and couldn’t make it in. In blue collar Pittsburgh people complained and moaned, but accepted this off new restriction, filling up their cars whether they needed to or no, because —because you just never know.

My father sat in our family room emitting gas burps, us children hanging around—too scared to move far away—what would happen next? We hung on over the arms of the sofas and lay on the floor between his chair and the coffee table, even though we were scared that one of those burps would come out in a blast of fire, like a dragon in one of our books, scorch our brows or even burn our house down; we still huddled around. We knew the word “combustion.” We begged him to put his martini down and drink the milk we had poured for him, its white creaminess our only hope. Surely, milk would help.

He smoked his cigarettes and pooh poohed us. Made fanning motions with his hands—not to dissipate the fumes but to shoo us away. “I got this,” he said, as he took another sip, pierced an olive with bravado, took another drag. “I’ m having your mother light them for me she said.” And our mother, with a shrug and giggle, fanned us away, too. She sat on the ottoman at his feet with her Manhattan, and said, “I just hope it doesn’t sting too much when he pees” and then laughed and laughed at her own raunch, feigning chagrin. Sometimes bring it back up is worse than letting it work itself out.

Somehow, this memory of sitting vigil around my Dad, waiting for the gas to work its way out of him, however that would look, makes me think about our tiny 14-pound miniature poodle—I’d like to be clear that we didn’t poodilize our poodles, but left them floppy mops of yarny loops. Our puppy, as he would forever be a puppy, went under my older brother’s bed and found a bag of pot, dragging it through the second floor hallway, eating much of its contents, tossing it everywhere. I don’t remember which of us saw it first, but Frisky was still wrestling with the bag, the scene was obvious and frightening. Frisky ate the marijuana. The classic dilemma befell us: we didn’t want to get in trouble, or get Jerry into trouble, but we had to tell our parents—we needed their help.

My Dad called the vet before he even spoke to us; we knew that he was our Dad and that he would know what to do. But, the vet told him that there was nothing to be done—Frisky would puke and poop and before that, he would be stoned. The vet said that ultimately, our dog would be fine. We had to wait it out.

Dad came upstairs and went in Jerry’s room; he had to do something, so this was it. As soon as the door was shut we crept out of our rooms and gathered in the hallway, having to listen in to how Dad was possibly going to handle this. “Do you realize the shame you just put us through, Jerry. I had to call the vet and admit that this family had pot in its house. Do you know how that feels?” I couldn’t see through the door, of course, but I imagine that he had his martini in one hand, his cigarette in the other, just like when he burped gas ethers for hours. Do I put these props in his hands in my head or were they really always there? And Jerry said the same thing, “This will pass. He’s going to be fine.” Dad wanted remorse from him and Jerry wouldn’t give it, confident that the dog would be fine.

Unlike the rest of us, who sniffled in the hallway everytime Frisky raced past us, his eyes not registering, not stopping for his name, his puppy heart revved up, as he traced the blueprints of our home, down the L shaped staircase around the banister into the forma living room, fast shot into the alcove and then a lap around the dining table. A short burst into the powder room, a longer run in the family room and then boom, back up again, the L shaped steps the L shaped hallway, where we stood, waiting each time to see if he’d look any different , if he’d slow down when he’d hear our coo’s of “Frisky, Frisky. Come here baby, It’s ok baby,” with hands promising unlimited scratches outstretched.

I don’t know how long this went on. Dad trying to pinch regeret from Jerry, Jerry standing firm that this was “no big deal,” the four of us other kids listening to Friskie when we couldn’t see him, his mad romp as he outlined the house parameter of the house again and again.

Finally, in the long part of the L of the 2nd floor he stopped, he convulsed and puked green, right in front of door to the room I shared with my sister. I hit the ground like I was the one puking and Friskie passed out less than an inch from his pile of play-do green puke.

Again we were yelling for Dad before we consulted with each other on what to do. This was not a situation we could manage, too alien and important really, considering Jerry had broken the law and maybe our dog, and Dad sounded sincerely upset about having to tell the vet that there was pot in our house. Dad came out and saw the scene and knew exactly what was happening. He told Jerry to get rags and a bucket and clean up the puke. He assured the rest of us that the doctor had told him that this is what would happened next, that we should be glad that this happened and it was out of his system. I lie down on the other side of his puke pile and lifted one of Friskie’s eye lids, I needed to make sure the the colored parts were right there and not rolled up in his head, I needed especially to make sure that he was mostly still here.

That’s how we spent the night. I slept half in and half out of my own doorway, face to face with my dog, opening up his eyes lid by lid, looking in and making sure he was still Frisky.

I lie on the floor in the doorway, face to face with my poor dog, and doing my best to avoid the damp spot that Jerry had cleaned up. My cheek getting impressions on the dark green embossed wall-to-wall in the hallway, my torso and legs on the pink and white variegated shag rug of my bedroom. Every time I drifted off, I was afraid I missed something, and I’d pull Frisky’s eyelids up, making sure his eyes weren’t rolled into the back of his head, make sure he looked like he was still with us.

Sometimes bringing it back up is worse. Sometimes you have to just wait for it to pass.